Postcards from the Edge: Iggy Pop and James Williamson's Kill City

A loving tribute to the lesser known entry from the Stooge's golden years

It’s easy to forget these days, when we might think of Iggy Pop as the goofy grandpa making faces with his parakeet on Instagram or talking about the good life with Anthony Bourdain over health food, but back in the early 1970s, Iggy, born James Osterberg, was a very Bad Person. And not by a 2020s-era moral rubric. He had multiple underage girlfriends (although this certainly doesn’t make him unusual in the panoply of 70s-era rockers), at least one of whom he turned onto drugs, he himself being an on-and-off heroin addict. He also, by many reports, turned The New York Dolls’ Johnny Thunders onto dope, an addiction from which the guitarist would never recover. To pay for his habit, Iggy cajoled and/or ripped off his bandmates and friends. When that didn’t work, he cashed fraudulent checks at a local record store, a crime for which his father had to refund the money in full. Angela Bowie, former wife of David, remembered Pop as, more or less, a sociopath - a highly intelligent manipulator who knew how to cadge what he wanted out of anyone. When original Stooges bassist Dave Alexander drank himself to death in early 1975 at the age of, of course, 27, the singer broke the news to his surviving bandmates by saying, “Zander’s dead and I don’t care, ‘cause he wasn’t my friend anyway.”

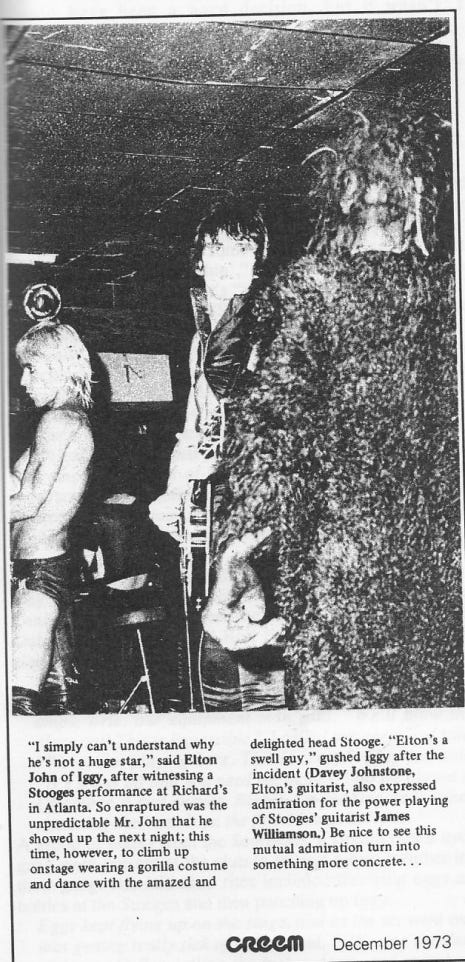

By that time, Iggy, himself 27 years old, was a has-been twice over. The Stooges had been rescued from obscurity after two low-selling efforts on Elektra Records singlehandedly by Bowie, who signed them to a deal with MainMan, his production company with manager Tony DeFries. Moving to England, they renamed themselves Iggy & The Stooges and set to work on Raw Power, released by Columbia in 1973. The album went nowhere, Bowie lost interest and agreed to MainMan’s suggestion they drop the band. Adrift, the Stooges desperately tried to salvage the situation by signing with new management and touring relentlessly, but trouble seemed to follow the band. Pianist Bob Sheff, alias “Blue” Gene Tyranny, quit the group after only two appearances when every other band member borrowed so much money from him that he was left in the red. Guitarist James Williamson, whose vicious guitar tone and distinctive riffs anchored all of the Raw Power material was unceremoniously dismissed at management’s suggestion, only to be brought back days later when his replacement, a gentleman going by the name Tornado Turner, didn’t stack up. “From now on, I was watching my back,” said Williamson. Meanwhile, Pop had already alienated Ron and Scott Asheton, his rhythm section he’d already attempted, and failed, to replace - especially Ron, who’d been demoted from guitar to bass and left uncredited for his writing contributions to the recent material. In line with the chaos, Iggy seemed to be coming unhinged to the point where even those closest to him couldn’t tell if it was an act or not. A comedy of errors unfolded at various gigs: projectiles hurled at the stage were common, as they were the other way ‘round - one night Iggy threw a watermelon into the audience, concussing a female attendee; another night, the singer, after snorting an elephant line of what ended up being PCP, was virtually unable to stand up, much less perform, before being left by his bandmates in a bush outside their hotel; at another venue, while diving off the stage and expecting to surf atop the crowd’s hands, Iggy instead fell face forward when the crowd parted “like the Red Sea”; most bizarrely, an Atlanta appearance was interrupted by overeager fan Elton John, who ambled onstage in a gorilla suit, terrifying Pop.

Returning to Michigan in February of 1974, the Stooges disintegrated in typically spectacular fashion. At a warm-up gig in advance of their homecoming appearance at Detroit’s Michigan Palace, the band played, according to critic Lester Bangs, a 45-minute rendition of “Louie Louie.” Iggy then picked a fight with a biker in the audience. The biker kicked his ass, ending the show. Over the radio the next day, Pop either challenged said biker’s gang, The Scorpions, to a rematch, or The Scorpions called into the station to say they were going to kill The Stooges, or both. Whatever the case, bedlam ensued at the Michigan Palace, all documented on live album Metallic KO, “the only rock album I know where you can actually hear hurled beer bottles breaking against guitar strings,” wrote Bangs. By this time, the band’s music, at Pop’s behest, had become a savage, violent proposition. Raw Power alienated mass audiences with its embrace of explicit sexuality and psychological darkness in tracks like “Search & Destroy,” “Penetration” and “Your Pretty Face is Going To Hell,” but in the wake of the album’s failure, Pop doubled down, pushing the material into comic vulgarity over Williamson’s chugging, proto-metal riffs. By their last appearance, the setlist included songs like “Rich Bitch,” “(I’ve Got A) Cock in my Pocket,” as well as the aforementioned re-write of “Louie Louie,” in which Iggy, playing off the rumor the Kingsmen’s hit rendition was secretly profane, sang explicitly profane lyrics in lieu of Richard Berry’s. As the cover’s final notes ring out on Metallic KO, Iggy says, “Thank you to whoever threw this glass bottle at my head. You nearly killed me, but ya missed again. Keep trying next week.” And with that, another glass bottle shatters off-mic. But there was no next week.

Defeated, the band returned to their adopted home of Los Angeles and broke up. Free from the band, Iggy’s prospects dwindled further. He became a de facto gigolo, living off his good looks and sexual prowess in exchange for food, shelter and drugs from any woman that would have him. If he couldn’t find a sugar mama, he slept outside. When unable to score heroin, he turned to quaaludes, alcohol, LSD, and whatever else he could get his hands on. He briefly considered auditioning to be the lead singer of KISS, if you can believe it, but didn’t show up to the audition. At some point, a collaboration with Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek was proposed. At a July tribute to Jim Morrison at the Whiskey-a-Go-Go, a relatively sober Pop - he even kept his shirt on - joined Manzarek and band for a few Doors covers, going over well with the audience. Manzarek rightly recognized Osterberg as an inheritor to the attitude and sensibility of his late bandmate Morrison; Iggy, in turn, had been inspired early on by a Doors concert in which Morrison verbally provoked the audience. Privately, Jim even held out hope he’d be asked to front a rebooted Doors. But none of it was to be. A tentative meeting with famed record executive Clive Davis ended in disaster when Pop showed up in his underwear, two hours late and very stoned. “I guess some things never change,” laughed Davis. Iggy then drafted Williamson into the new project, but Manzarek, already weary of the singer’s split personality, bowed out, feeling there was “no sonic space” in the mix with the guitarist’s Les Paul. Iggy protested that he’d lose his audience without James’ searing riffs. “What audience?” came the keyboardist’s reply.

Instead, Iggy made his official return to the stage at Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco with an ad hoc group of local glam musicians, a musical play billed as “The Murder of a Virgin.” With a two-chord musical background based on The Velvet Underground’s “Some Kinda Love,” the performance climaxed when he instructed Ron Asheton, decked out in full (and authentic) Nazi regalia, to beat him with a whip. Covered in blood, Pop then hurled racial epithets at a black concertgoer to provoke him into stabbing him with a rusty knife, but failing that, carved an “X” into his own chest. Not long after, he was arrested for public intoxication after ingesting one too many quaaludes before heading to a local hamburger joint.

As Iggy learned years ahead of his imitators, there is a limit to nihilistic behavior and artistic decadence, on the other side of which lies self-parody and self-destruction, and by 1974, he had hit it. Needless to say, he was commercially adrift, as well. Glam was on the way out, heralded by Bowie’s “retirement” of Ziggy Stardust the previous year, and punk had yet to be born in its wake. The Stooges had utterly failed to capitalize off Bowie’s endorsement of their music, unlike fellow proto-punk Lou Reed, who, despite going through his own darkness, had translated the superstar’s support into international fame with LPs like Transformer, Rock & Roll Animal and Sally Can’t Dance. Not only that, Pop had been bested at his own game commercially by Alice Cooper, who changed their sound and style radically after a move to Detroit. “They did a gig with the Stooges, and three months later, they were our neighbors,” said Iggy in the Motor City’s Burning documentary. “All of a sudden it was, ‘Under My Wheels’ and ‘[I’m] Eighteen’…and they killed us. They took our themes, articulated ‘em well enough, threw all the crazy shit out…and they did the units.” Cooper’s winning image became that of the madman, excommunicated from, and considered “sick and obscene” by, polite society; Iggy actually was all those things, but industry-wide, he was seen as something between a joke and a monster. Clearly, a re-assessment, both aesthetically and personally, was long overdue. Following his arrest, he was given the choice of jail time or the psych ward; Iggy wisely checked himself into the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Unit. “I’ve been addicted for a long time to very heavy drugs. Now I’m a fool who uses pills and slobbers a lot,” he said to the intaking intern. “Would you help me? Could you lock me up here where none of my so-called friends can get to me?”

The moment marked the turning point in not only Pop’s career, but his entire life. Placed under the care of Dr. Murray Zucker, Osterberg was slowly brought back from the edge. The psychiatrist, finding Jim likable, was able to see through his rock-and-roll narcissism enough to diagnose the singer with hypomania, a form of bipolar disease common among artists and writers, with examples such as van Gogh and William Blake. While there were detours - at some point Bowie showed up with either Dean Stockwell or Dennis Hopper in tow (depending on who’s telling the story) and broke out the cocaine; another time Iggy was on the precipice of walking away from the psychiatric unit, and his career, to apply for a job at McDonalds - the singer responded to the treatments to the point where he was allowed day leave to work on a new record with Williamson.

Ensconced in James’ apartment at The Coronet, a condemned building that neighbored the infamous “Riot House” Hyatt on the Sunset Strip, Pop and the guitarist had built up a set of eight songs. With James playing through a practice amp and Iggy cupping his hand over his mouth to sing, they reworked a couple of the less controversial numbers from the last Stooges sets, “I Got Nothin’” and “Johanna,” to round out a set of material that took Williamson’s riffage and Pop’s lyrical minimalism into new and - dare I say - more mature territory. The pair produced one of the first noir-rock albums, if not the first: Kill City, a gritty portrait of Los Angeles circa 1975 that still, in many ways, rings true today, and stands alongside Love’s Forever Changes, The Germs’ (GI) and The Doors’ L.A. Woman as some of the finest music ever made about the place. But unlike Arthur Lee’s acid-soaked Fellini-esque visions or Jim Morrison’s beat poetry aspirations, Iggy used the lens of Raymond Chandler to depict the Los Angeles he saw at street level.

Take the title track, which has about seven lines of lyrics total:

I live here in Kill City, where the debris meets the sea

It’s a playground to the rich, but it’s a loaded gun to me

and later,

The scene is fascination, and everything’s for free

’Til you wind up in some bathroom, overdosed and on your knees.

Quite a far cry from the last we heard from Ig on Raw Power’s closer “Death Trip,” “Baby, I wanna to take you out with me/Come along on my death trip” - which, in an interesting parallel had him chanting “Turn me loose, turn me loose on you,” now echoed in the backing singers’ refrain on “Kill City,” “Give it up, turn the boy loose!” Here, the death trip ends in real physical death, and an ugly one in an ugly place. Beyond the grit, there’s a real vulnerability to Iggy’s lyrics and performance, revealing the ultimate destination of rock-and-roll decadence, no longer romanticized.

Pop managed to revamp “I Got Nothin,” from the somewhat ab-libbed sounding down-and-outsville lyrics on Metallic KO into a hangover song on par with Kevin Ayers’ “Shouting in a Bucket Blues” or even “Touch of Grey.” It’s the sound of the sun coming up on a scene that would rather shy away from daylight, delivered in one of Iggy’s most moving performances, his voice whispering, sometimes cracking:

Man, I feel, feel so washed out today

Burn the sheets off my bed, man,

And throw that girl away

I got nothin', got nothin' today

Man, I feel, feel so used inside

Broken hearts and leather and empty pride

'Cause I got nothin', I got nothin' to say

Before ending on a bridge that takes the hangover into the realm of apocalypse, a Hollywood walk of shame with a chilling self-portrait of the singer, and his worldview:

I see you young girls coming down the road

But you ain't got any chance against the things I know

Out of the cradle, straight into the hole -

Nothin'!

There’s a real tension across the material between the temptation of a tried-and-true nihilism and some kind of movement towards love, both platonic and romantic. “Sell Your Love” is an explicit paean to the urban streetwalker, at turns sympathetic, others scornful, in which Iggy refrains, “You sell your love off, baby/You push your love till nothings's left.” In “Beyond The Law,” an us-against-the world anthem written, according to biographer Paul Trynka, in tribute to Manzarek, Pop sings, “We get no ‘V’ for victory, we don’t stand for nothin’” as not only a badge of honor, but a bond of brotherhood. In “Johanna,” Pop invokes a toxic perma-doom relationship, hollering, “I hate ya, baby, ‘cause you’re the one I love!” - the effect is akin to hearing the neighbors fighting next door. And then later, in one of the most beguiling tunes in his discography, comes the last verse of “Consolation Prizes,” making keen reference to Ig’s Bad Reputation but with a certain kind of backhanded affection towards a special someone in his corner:

Teen magazines won’t let me be

And now I feel so clean, but they’re always diggin’ dirt on me

Through the lonely nights, just thinkin’ -

She’s sweet, my consolation prize.

Then, on the album’s most haunting track, “No Sense of Crime,” Iggy depicts a couple united by hard drug use, in which “drugs and death are our place and time,” capturing, in typically pithy fashion, the creeping horror of junkie ennui straight out of Skid Row:

Kids in pain, she sees them crawl

Now ain't that funny?

Kids in pain, she sees them crawl

She doesn't care at all.

Kill City exists in a world of broken dreams, broken people and degradation, but it’s not a setting devoid of hope, love or the promise of salvation. Even at its bleakest, the album seems to offer a quiet strength within the storm, if not any means of escape. Recorded within months of Iggy putting the breaks on a lifestyle that almost certainly would have led to further humiliation and a premature death, the album is a rarity in that it offers up a moment of self-reflection that’s neither sanctimonious nor superficial, an accurate glimpse into a moment of crisis and transformation. A rehab album worth listening to, in short. And it’s not devoid of humor, either - take the final vocal track, “Lucky Monkeys.” Over a vamp that curiously sounds pretty similar to The Velvet Underground’s “Some Kinda Love,” Iggy interrupts his own acid alliteration to take a swipe at the smoldering embers of the LA glam scene:

Boulevard cucarachas tryin' to look like Bowie

Tryin' to be sick as Mick,

Look out lucky monkeys!

…before the track concludes with an accelerando to almost double time under Iggy and a backing singer vocalist repeating, “I was born dead crazy/Born crazy/Born dead!,” slowly falling out of time with the backing track. It’s one of the most demented sign-offs to a rock album that I know. And considering the history of the piece - which most likely had its origins in the horrific “Murder of a Virgin” performance months prior - it’s an interesting coup. The singer, rather than destroying or martyring himself for Rock and Roll (as local creep/pop genius Kim Fowley portrayed it) has instead resigned to accept himself in all his fucked-upedness: a lucky monkey, born crazy.

And the best part about this story is, he survived. Rather than being an epitaph or a hollow attempt at rehabilitation, Kill City stands as a totem of where things turned around for Iggy Pop. Some months after completing the tracks, Bowie spotted Pop walking down the sidewalk from his limo. The two rekindled their friendship under less frenetic circumstances, and soon, Iggy joined David on the Station to Station world tour before ultimately moving in with him in Berlin. He’d be the musical guinea pig for Bowie’s burgeoning musical experimentation on 1976’s The Idiot before the two completed Iggy’s last great album, 1977’s Lust For Life, the ultimate consolidation of Osterberg’s musical strengths.

Most amusingly of all, his rebound was accompanied by the greatest revenge for a once-unappreciated artist: an undeniable impact on popular culture. Right as Iggy was emerging from the psych ward, innumerable bands were turning to The Stooges’ albums for inspiration, their groups fronted by manic, often shirtless, wildman lead singers. Within just a few years, there would be multiple Iggy Pops on stages around the world: The Birthday Party’s Nick Cave, The Damned’s Dave Vanian, The Germs’ Darby Crash, The Cramps’ Lux Interior, The Gun Club’s Jeffrey Lee Pierce, Flipper’s Bruce Loose and Will Shatter, Black Flag’s Henry Rollins, The Dead Boys’ Stiv Bators, GG Allin. The list goes on, and it’s still being added to today.

Kill City was recorded, as one might suppose, under clandestine circumstances. CREEM journalist Ben Edmonds had spurred on the project, hoping to prove The Stooges could make “real music,” and helped Pop and Williamson scam time at Jimmy Webb’s home studio. He even almost got the pair signed to Seymour Stein’s Sire Records - just in advance of the mogul signing The Ramones, Richard Hell, Talking Heads and Madonna - but, “snatching defeat from the jaws of victory,” the two stole the tapes in hopes of a better deal. The album, of course, went nowhere. But a couple years later, looking to capitalize off Iggy’s renewed notoriety, Williamson did a quick-and-dirty mix of the material for release on Greg Shaw’s BOMP Records.

Consequently, Kill City, in its original form, is raw and wild. Drums sound like they’re pumping from the back of a garage. Williamson’s nuclear-level Les Paul is only dialed back a little from its Raw Power maximum, typically front and center in the mix. (Also, I’d be beyond remiss to not point out how amazing James is on this record - the last record he wrote and played on for almost 40 years. He’s like a turbo-charged Keith Richards, always matching the tone of the lyrics with these utterly unique riffs, like the oblong slide on “Consolation Prizes” or the utterly spine-tingling open string acoustic voicing on “No Sense of Crime,” or the walk-down strut of “Johanna,” and so on, and so on….) Vocals seem to emanate from different sonic spaces entirely - Pop will at one moment sound like he’s shouting through a police bullhorn, then be whispering in your ear the next bar. Faceless, muffled backing vocals dot in and out, as do overly loud sax solos and even the occasional, inexplicable synthesizer. But given the psychic mess that birthed the material itself, it’s perfect: the band’s almost falling apart, Iggy has already fallen apart and the tape can barely contain the chaos, but there’s still beauty within the eye of the storm.

Williamson would later complete a more controlled remix that highlights the brilliance of the material over the anarchy of the circumstances surrounding its creation, but Kill City remains a less-celebrated moment within Osterberg’s discography - perhaps down to its release on an indie label, perhaps due to the intensity of the material within, perhaps due to Pop’s ongoing ambivalence regarding the record (to say nothing of Williamson’s handling of its release); hard to say. But it’s still a remarkable moment within a remarkable winning streak: between 1969 and 1977, Iggy Pop didn’t make a bad record, and every release revealed a new dimension to his minimalistic, balls-out approach to music. Let Kill City, then, stand as his secret singer-songwriter album alongside the free jazz freak outs of Fun House, the metallic primordial soup of Raw Power and the user-friendly accessibility of Lust For Life - the triumphant title track of the latter containing a sly wink to his mid-70s dog days:

I'm worth a million in prizes

Yeah, I'm through with sleeping on the sidewalk

No more beating my brains

No more beating my brains

With the liquor and drugs

With the liquor and drugs

Thank you to Vera Amanda Allan and Ray Seraphin for helping me think through parts of this post.

Bibliography:

Trynka, Paul: Open Up and Bleed, Broadway Books, 2007.

McNeil, Legs and McCain, Gillian, Please Kill Me, Grove Press, 1996.